| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Danger &

Despair's |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Screenings |

|

| |

|

|

| |

in Vintage 16mm Film |

|

| |

THE COPS ARE COMING! |

|

| |

THE COPS ARE COMING! |

|

| |

Yes they're coming....

|

|

| |

on Thursday Nights in

July |

|

| |

|

|

| |

With a new series

|

|

| |

programmed by Abby

Staeble |

|

| |

|

|

| |

FREE admission with

reservations |

|

| |

screenings@hotmail.com |

|

| |

June Vincent &

Dan Duryea in 'BLACK ANGEL' 1946 |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

- The

Cops are Coming!

“Lets get out of here--the cops are coming.” If that sentence

strikes fear in your heart, don’t panic. In this series of three

films we’ll be shining the light in their eyes. We’ll be taking a

look at the various ways in which the films’ portrayals of police

deviate from the norm of their time.

The norm was shaped by the Production Code, developed in the 30’s,

in large part as a response to America’s love of the gangster, a

love fueled by the glamorous, criminal sociopaths depicted in

gangster films like Little Caesar (1930), The Public Enemy (1931)

and Scarface (1932). Authorities feared that such colorful

characters would spawn juvenile imitators and generally lower the

moral standards of an America easily swayed by the cinema.

The Code was given teeth in 1934 when the Catholic Church literally

put the fear of Hell into would-be viewers of films condemned by the

Church’s Legion of Decency. The loss of Catholic box office revenue

would mean that glamorized sex and crime would no longer pay, and

that would have been Hell for Hollywood. So Hollywood cleaned up its

act: Producers, industry-wide, required that all films be given a

seal of approval from the Hays-Breen Office. Releasing a film

without the seal would subject studios to a $25,000 fine and worse

still--the films would be barred from playing in the vast majority

of first-run theaters that were members of the Motion Picture

Producers and Distributors of America.

The seal was only granted when the Breen Office’s censors felt a

film met the Production Code’s three: “General Principles” namely,

that:

1. No picture shall be produced that will lower the moral standards

of those who see it. Hence the sympathy of the audience should never

be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin.

2. Correct standards of life, subject only to the requirements of

drama and entertainment, shall be presented.

3. Law, natural or human, shall not be ridiculed, nor shall sympathy

be created for its violation.

Whether the police were sympathetically treated in a film was among

the key factors systematically reviewed by the censors. See the

attached first page of the standard report form used by the Breen

Office during the 1940’s

*1, reproduced from James Naremore’s More Than

Night- Film Noir in its Contexts. As a result, in the vast majority

of films produced during the Code’s restrictive reign, when the

police arrive on the scene, they are characterized as moral and

ethical men enforcing a just law

*2. This is borne out by an analysis

of the top ten grossing films for each year between 1946 and 1965

conducted by Powers, Rothman and Rothman for their book, Hollywood’s

America: Social and Political Themes in Motion Pictures. Further,

only one in ten police characters included in this study resorted to

violence. *3

- *1. Naremore, James.

More Than Night- Film Noir in

Its Contexts. Berkeley: University of California

Press. 1998

*2. Crawford, Charles. “Law Enforcement and Popular

Movies: Hollywood as a Teaching Tool in the Classroom.“

http://www.albany.edu/scj/jcjpc/vol6is2/crawford.html

3. Powers, S., Rothman, D. & Rothman, S. Hollywood's

America: Social and political themes in motion

pictures. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. 1996, p.107, as

sited in the Crawford article.

|

|

| |

Programming & All Film Notes by Abby Staeble |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

All

Films at a NEW show time 7:00 pm - Full BAR and Doors

open at 6:00 pm |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Thursday

July 5th - 7:00 pm |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

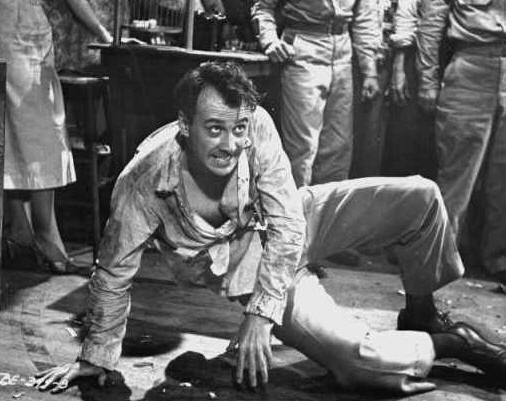

'WHERE THE SIDEWALK ENDS'

1950 - B&W

|

|

With:

Dana Andrews, Gene Tierney, Carl Malden & Gary Merrill |

| |

|

| Directed

by Otto Preminger Script: Ben Hecth |

| Photgraphy:

Joseph LaShelle Costumes: Oleg Cassini |

| |

He’s the cop. He’s the

criminal. He’s the cop. He’s the criminal. He’s the cop and the

criminal.

In Where the Sidewalk Ends producer and director Otto Preminger reunited

Laura’s Gene Tierney and Dana Andrews. But the intervening six years had

not been kind to their characters. They no longer lounge in the

overstuffed chairs of the wealthy pining for an unrequitable love. They

now live in decidedly meaner streets. Tierney’s character has been

saddled with an abusive husband. Andrews’ Mark Dixon is weighed down by

fear and self-loathing of his own sadistic nature. Tierney defends

herself with a self-deceptive giddy optimism, a defense so eggshell

fragile in its inappropriateness that it is painful to watch. Mark Dixon

punches back. |

| |

| |

|

Anyone using the Breen Office standard report to keep score on Where the

Sidewalk Ends is likely to agree with James Naremore who finds it

amazing that the film, among many other notable noirs, was produced at

all. Ben Hecht’s script and Dana Andrews’ tight-lipped portrayal give us

a Mark Dixon who is a brutal, ticking-time-bomb of a policeman -- hardly

the image of the virtuous upstanding law enforcer wished for by the

censors. And then, how would the censors have felt about Karl Malden’s

cold, by-the-book cop, Lt. Thomas, who is far less sympathetic than the

self-tortured Dixon.

Nonetheless, released in 1950, Where the Sidewalk Ends was given the

seal of approval and appears to have opened the flood-gates to a spate

of noir rogue cops films that includes: The Prowler (1951), The Man Who

Cheated Himself (1951), On Dangerous Grounds (1952), The Big Heat

(1953), City that Never Sleeps (1953), Rogue Cop (1954), Pushover

(1954), and Touch of Evil (1958).

Perhaps Where the Sidewalk Ends was an intentional baiting of the

Production Code. It was released at a time when the Code was losing its

effectiveness due to a number of factors including the forced

divestiture by the major studios of their theater chains. Otto Preminger

is renowned for his flaunting of the Code a few years later. His 1953

comedy, The Moon Is Blue was not given the Breen Office seal of approval

because he refused to cut the words “pregnant,” “virgin,” and “seduce.”

In 1955 his The Man with the Golden Arm was not given the seal of

approval because it violated the Code’s prohibitions against depictions

of drug use. The films’ critical and popular success despite their

release without the seal helped pave the way for the end of the

Production Code and the switch to a rating system. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Thursday July 12th - 7:00 pm |

|

|

|

|

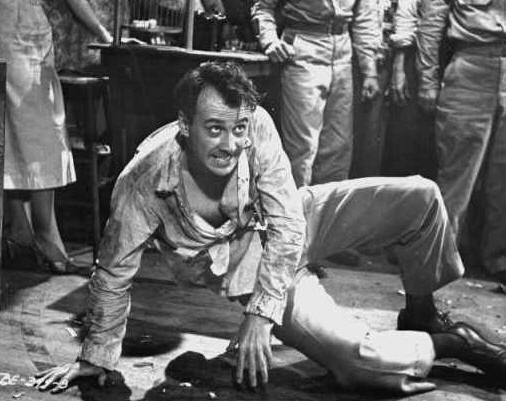

'BLACK ANGEL'

1946 - B & W

Universal Pictures |

|

With: Dan

Duryea, June Vincent & Peter Lorre |

|

Directed:

Roy William Neill Script: Roy Chanslor Story:

Cornell Woolrich |

|

|

|

Beautiful, no good nightclub

singer Mavis Marlowe is strangled to death. Kirk Bennett is accused. “I

didn’t kill her,” he says. “Then you got nothin’ to worry about,”

responds Capt. Flood (Broderick Crawford). Catherine, Bennett’s angelic,

house-frau wife played by June Vincent, continues to believe in her

philandering husband’s innocence despite a good deal of evidence to the

contrary. Hoping to find proof, she enlists the aid of Mavis’s jilted

alcoholic husband, Martin Blair, who, surprisingly, is sympathetically

and sensitively portrayed by Dan Duryea (at least it’s a surprise to

those who remember Duryea best playing misogynistic villains and pimps.)

Martin is a brilliant piano player. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Catherine’s voice is at

least as beautiful as that of the murdered Mavis (no surprise

there--June Vincent sings her own character’s songs and Mavis’s, too.)

Martin and Catherine exploit their musical talents in their efforts to

trap the real killer. As he sits waiting on death row, Kirk Bennett

better hope that the unlikely duo are more persistent than Capt. Flood

who is “three months behind in unsolved homicides,” and refuses to

investigate any further. Based on a Cornell Woolrich novel, the film is

chock full of dark twists and irony leading to an exciting conclusion

filmed in a wonderfully subjective style. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The less-than-zealous Capt.

Flood barely skims the surface of Woolrich’s deep disdain for the

police. Consider this description of Woolrich’s 1935 short story “Dead

on Her Feet” from the Francis M. Nevins, Jr. biography, Cornell Woolrich:

First You Dream, Then You Die. Plainclothesman Smitty is sent to pull

the plug on a dance marathon …

… only to find that one of the last dancers on the floor has literally

died in her partner’s arms. She was desperate to win the $1,000 prize

and had been dancing for nine days and nights, but it wasn’t exhaustion

that killed her: the ambulance doctor finds that she’s been stabbed in

the heart with a metal pencil while reeling dazedly around the dance

floor. Smitty begins his investigation by publicly beating up the dead

girl’s dance partner and fiancé, and ends it, even though he knows by

this point that the fiancé is innocent, by forcing him to dance with her

corpse in his arms until he is literally driven insane. What was

Smitty’s motivation for this obscenity? He had none. Needed none. He’s a

cop. For Woolrich that means he is the earthly counterpart of the

malevolent forces that rule our lives.

*4

It is most unlikely that any filmic depiction of Smitty would have

received the Breen Office’s seal of approval. Arguably, however, Smitty

represents less of a danger to the pro-establishment world viewpoint the

Breen Office and its Production Code sought to uphold than Black Angel’s

dispassionate Capt. Flood. Smitty is an aberration, a bad apple, and our

expectation is that eventually the predominant forces of fate and/or

justice would weed him out -- order would be restored. At least that’s

the standard fate of rogue cops in films like Where the Sidewalk Ends

and The Prowler. But overworked and apathetic Capt. Floods are a dime a

dozen and still around at the end of the film. Thus, Black Angel

insidiously creates the impression that like Martin and Catherine, we

are left to our own devices to defend ourselves against a world of

murderers, philanderers, and Korsikoff’s psychosis. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

*4. Nevins Jr.,

Francis M. Cornell Woolrich: First You

Dream, Then You Die. New York: Mysterious Press.

1988, p 134. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Thursday

July 19th - 7:00 pm |

|

|

|

|

|

'THE PHENIX CITY STORY' 1955 - B& W Allied

Artists |

|

With: Richard

Kiley, John McIntire & Kathreen Grant |

| Directed

by Phil Karlson Script: Crane Wilber & Daniel

Mainwaring |

| |

|

The Phenix City Story is a

noirish docu-drama complete with a story line stolen from the headlines,

authoritarian voice-overs, and location shooting, but if you’re looking

for a police procedural in the vein of The Naked City or He Walked by

Night, where techno-savvy law officers cleanse the city of its criminal

elements, you’re in the wrong city. It is also a returning veteran

story, but if you’re looking for a case of a confused veteran arriving

home to find his world has changed (think The Blue Dahlia) you’re in the

wrong city. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The problem with Phenix City is that it hasn’t changed. In this telling

of a “true story” John Patterson returns home from the Nuremberg trials

where he helped bring Nazis to justice to find that his hometown has

remained the same vice-ridden place it’s been for generations. The only

new twist is that the syndicate has taken over the show and modernized

operations.

Half the town’s citizenry are seemingly willing participants in the

rigged gambling, prostitution and violence that’s taking place right out

in the open. Factory workers efficiently turn out loaded dice and marked

cards. Good girls deal the marked cards while the bad girls peddle

themselves on the street. The police are not merely disinterested; they

are paid for tasks like clearing out any losers who have had the bad

sense to object to the stacked odds. Those citizens who are not actually

participating in the corruption, with sadly few exceptions, simply look

the other way. That’s clearly the safest course. While the mob has

introduced corporate efficiency to corruption, it relies on time honored

intimidation tactics to protect its turf.

The brutality of the intimidation and the seediness of the corruption

are convincingly conveyed—fully honoring the Production Code’s tenet of

not glorifying crime. Brilliant framing and editing make us feel every

cheap gut punch, hold our breath against the fetid atmosphere, and

generally convey a real sense of you-are-there documentary (with one

exception where the investment in a more convincing dummy was definitely

warranted). Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the film is that the

perpetrators and victims of all this violence and squalor are the most

banal looking of individuals. The kind of people we see in the

supermarket or sit next to on BART.

The film is introduced by news interviews with real life citizens of

Phenix City who were involved in the “clean-up” of the town which the

dramatized portion of the film prequels and with which the public would

have been familiar through headline news stories of the day. These

interviews are slow-going, but they serve several purposes. The

interviewees are not heroic looking in any sense which, together with

the ordinariness of the characters in the drama, may be read to

underscore several contradictory messages imparted by the film.

One such message is that what happened in Phenix City could happen

anywhere where the public looks the other way in the face of encroaching

evil. Without the ordinary citizen’s vigilance an unchecked

establishment is easily corrupted and unreliable as a deterrent to evil

that can quickly spread to the point where it is invincible. This is a

message which could equally serve anti-McCarthyites or communist

witchhunters.

The message of the film which the Production Code office would likely

prefer is that Phenix City was in a sense a “rogue” city and the

corrupted police force an anomaly. The plot line follows the standard

rogue cop plot line. The ordinary man on the street would be unable to

fight the mob alone. The good guys, led by John Patterson, must call in

the establishment, in this case the National Guard, to cleanse the

otherwise virtuous state of Alabama of an isolated stain. Order is

restored. Never mind that as revealed to the American public by

televised investigations instigated by Senator Estes Kefauvers in1950,

the mob was now highly organized, corporatized and everywhere. Never

mind one of the interviewee’s pronouncements that at the time of the

interview the mob was already reasserting its tentacles in Phenix City.

In any event, the film propelled the real John Patterson into the

Alabama Governor’s office where he served several terms. Despite his

filmic friendship with the good Zeke Ward, according to Bullets Over

Hollywood author John McCarty, he became a staunch segregationist even

earning the Ku Klux Klan’s endorsement.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

- All Films

start at 7:00 pm - |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

ROBERT MARION Hosts the series which starts at a NEW TIME 7:00 pm. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

FREE ADMISSION - Luscious

Libations of all varieties - Doors & Bar open at 6:00 pm - Films at

7:00 pm |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

RSVP A MUST! Get on the

Door List to be admitted - Reserve a Seat. |

|

|

| |

|

Event location given with a

seat confirmation Contact:

screenings@hotmail.com |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The Thursday Night

Screenings are private film events, admission to these events is by

invitation only through a request and is |

|

|

| |

|

solely at the discretion of

Danger & Despair and the City Club! At least according to our attorneys

who tell us... |

|

|

| |

|

"

The Screenings are private

events!, ...and DON’T FORGET IT !! " |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

www.noirfilm.com |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

__________________________________________________ |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|